Financial Times: Why the Whole World Should Worry About Stablecoins

Article Author: Martin Wolf

Article Compiler: Block unicorn

A few months ago, my son’s father-in-law, who lives in New York State, sent a substantial amount of money to his family in the UK. However, the money took a long time to arrive. Worse still, there was no way to trace its whereabouts. His bank contacted the intermediary bank used, only to be told that the receiving bank in the UK—one of the largest banks in the UK—refused to respond to any inquiries. I asked colleagues what might have happened, and they suggested it could be related to money laundering. Meanwhile, my father-in-law was extremely anxious. Two months later, the money suddenly appeared in his account, and he had no idea what had transpired during that time.

This situation is in stark contrast to my previous experiences of transferring money between the UK and the EU. Across the Atlantic, remittances have always been reliable and quick. This may be one reason why Americans are keen to embrace "stablecoins" as an alternative to the banking system. Daniel Davies pointed out two other reasons: first, the cost of credit card payments in the US is relatively high (about five times that of Europe!), and second, the fees for cross-border remittances are exorbitant. Both reflect the failure of the US to effectively regulate powerful oligopolies.

In an article last month, Gillian Tett of the Financial Times suggested another motive behind the Trump administration's welcoming stance on stablecoins. US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent faced a dilemma: the US needs the world to hold vast amounts of US Treasury bonds at low interest rates. She pointed out that one solution is to promote the widespread use of dollar-denominated stablecoins, focusing not on the domestic market but on the global one. As Tett noted, this is advantageous for the US government.

However, these are not legitimate reasons to welcome dollar stablecoins. As Hélène Rey of the London Business School stated, "For the rest of the world, including Europe, the widespread adoption of dollar stablecoins for payments amounts to the privatization of seigniorage by global participants." This would be yet another predatory move by a superpower. A more reasonable choice would be for the US to turn to lower-cost payment systems and reduce extravagant government spending. But neither is likely to happen.

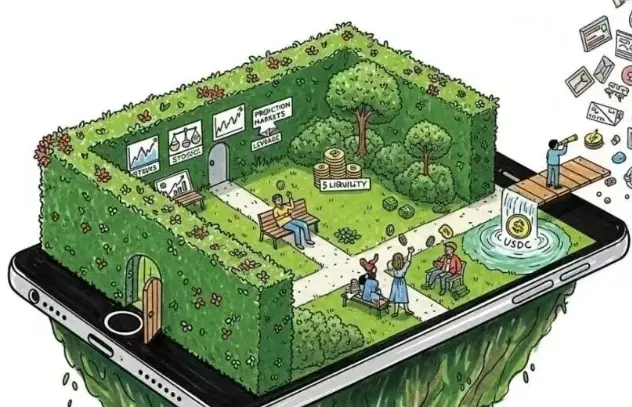

In summary, stablecoins—marketed as digital alternatives to fiat currencies (especially the dollar)—seem to have a bright future. As Tett pointed out, "Institutions like Standard Chartered predict that the stablecoin industry will grow from $280 billion to $2 trillion by 2028."

The future of stablecoins may indeed be bright. But should anyone other than the issuers, various criminals, and the US Treasury welcome them? The answer is no.

Indeed, stablecoins are much more stable than currencies like Bitcoin. But compared to cash dollars or bank deposits, their so-called "stability" is likely just a "scam."

The International Monetary Fund (IMF), the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), and the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) have all expressed serious concerns about this. Interestingly, the BIS welcomes the concept of "tokenization": they believe that "by integrating tokenized central bank reserves, commercial bank funds, and financial assets onto the same platform, a unified ledger can fully leverage the advantages of tokenization."

However, the BIS is also concerned that stablecoins may not pass the "three key tests of uniqueness, resilience, and integrity." What does this mean? Uniqueness refers to the requirement that all forms of a specific currency must be interchangeable at equivalent value at any time. This is the foundation of trust in currency. Resilience refers to the ability to facilitate payments of various sizes smoothly. Integrity refers to the ability to curb financial crime and other illegal activities. Central banks and other regulatory bodies play a core role in all of this.

Current stablecoins fall far short of these requirements: they are opaque, easily exploited by criminals, and their value is fraught with uncertainty. Last month, S&P Global Ratings downgraded Tether's USDT (the most important dollar stablecoin) to "weak." This is not a trustworthy currency. Private currencies often perform poorly in crises, and stablecoins are likely no exception.

Assuming the US intends to promote lightly regulated stablecoins, partly to consolidate the dollar's dominance and finance its massive fiscal deficit, what should other countries do? The answer is to do everything possible to protect themselves. This is especially true for European countries. After all, the new US national security strategy has openly indicated its hostility towards democratic Europe.

Therefore, European countries need to consider how to introduce a stablecoin in their national currencies that is more transparent, better regulated, and safer than the stablecoins that the US might currently propose. The approach taken by the Bank of England seems wise: just last month, it proposed a "proposed regulatory framework for systemic pound stablecoins," noting that "using regulated stablecoins can lead to faster, cheaper retail and wholesale payments and enhance their functionality, whether for domestic or cross-border payments." This seems to be the best starting point at present.

The current US leadership appears very enthusiastic about the tech companies' motto of "move fast and break things." In terms of currency, this could have disastrous consequences. Indeed, we have reason to leverage new technologies to create faster, more reliable, and safer currency and payment systems. The US certainly needs such systems. However, a system that makes false promises of stability, fosters irresponsible fiscal policies, and opens the door to crime and corruption is not what the world needs. We should resist it.